ACSA Conference Submission co-authored by faculty Sameena Sitabkhan and ARH 498 students Kim Ebueng, Lowai Ghaly, Mazen Ghaly, Andrew Hart, Mohamed Meawad, Kenny Soriano

Keywords: co-creation, micro-intervention, unhoused families, family shelter, community school

Micro-interventions can powerfully disrupt the systems that preclude an empowering experience in family shelters. Through co-creation, families can actively participate in the design research process. Valuing lived experiences of unhoused families removes the power imbalance between those with and without design training. Co-creation at the micro-scale prepares architecture students with skills to usher in change in the design practice.

EMERGENCY CONGREGATE FAMILY SHELTER

The Stay Over Program is an emergency congregate family shelter located in the gym of the Buena Vista Horace Mann K-8 Community School (BVHM) in San Francisco. The shelter’s 69 beds comprise 79% of all available congregate family shelter beds in SF.1 Congregate shelters are used as a last resort for families when there is no other temporary housing option available.

The number of unsheltered families fluctuates, so an estimate is based on a Point-in-Time (PIT) count. Conducted every two years using the HUD criteria, the count includes people in shelters, cars, and sleeping rough. The most recent PIT count was conducted on 2/23/2022 between 8pm and 12am. On this night, 7,754 people were counted of which 605 people were in families. Seventy-eight people in families were found to be unsheltered.2

SFUSD counts its unhoused students using a broader criterion, the McKinney-Vento Act, a federal law.3 The total count includes families temporarily staying with another family, living in homes without power or water or heat, in shelters, in weekly rate housing or motels, in abandoned buildings, cars, trailer park, campground, or on the streets. In 2022, there were 2,370 students experiencing homelessness.4

FAMILY SHELTER AT COMMUNITY SCHOOL

At the BVHM Community School, social workers connected behavior issues in three kindergarteners with their stays in congregate shelters for the general population.5 To support unhoused families at the school, the Stay Over Program was created in 2018 as an emergency family shelter. The non-profit shelter operator, Dolores Street Community Services (DSCS), worked closely with BVHM to create a warm and supportive culture leveraging the shared commonality of parents with school-aged children and their familiarity of the school grounds. The emergency shelter filled an unmet need at the community school to provide wrap-around services to meet the basic needs of the families.

NEED FOR MICRO-INTERVENTIONS

San Francisco public school capital improvements are frequently delayed by several years even after funding is approved. BVHM facilities are a century old and in dire need of improvements.6 In 2022, the school received $40 million in funding and construction was projected to be complete by the end of 2025.7 The schedule has been revised since with a new completion date of 2028.8

In the meanwhile, families with children sleep in the emergency shelter in less-than-ideal conditions each night. Improving the conditions is urgent as it impacts vulnerable young children during their critical developmental years. Micro-interventions, nimble and fast-paced, can leverage available resources to bring relief on a timeline of months.

WHAT NOT TO DESIGN / WHAT TO DESIGN

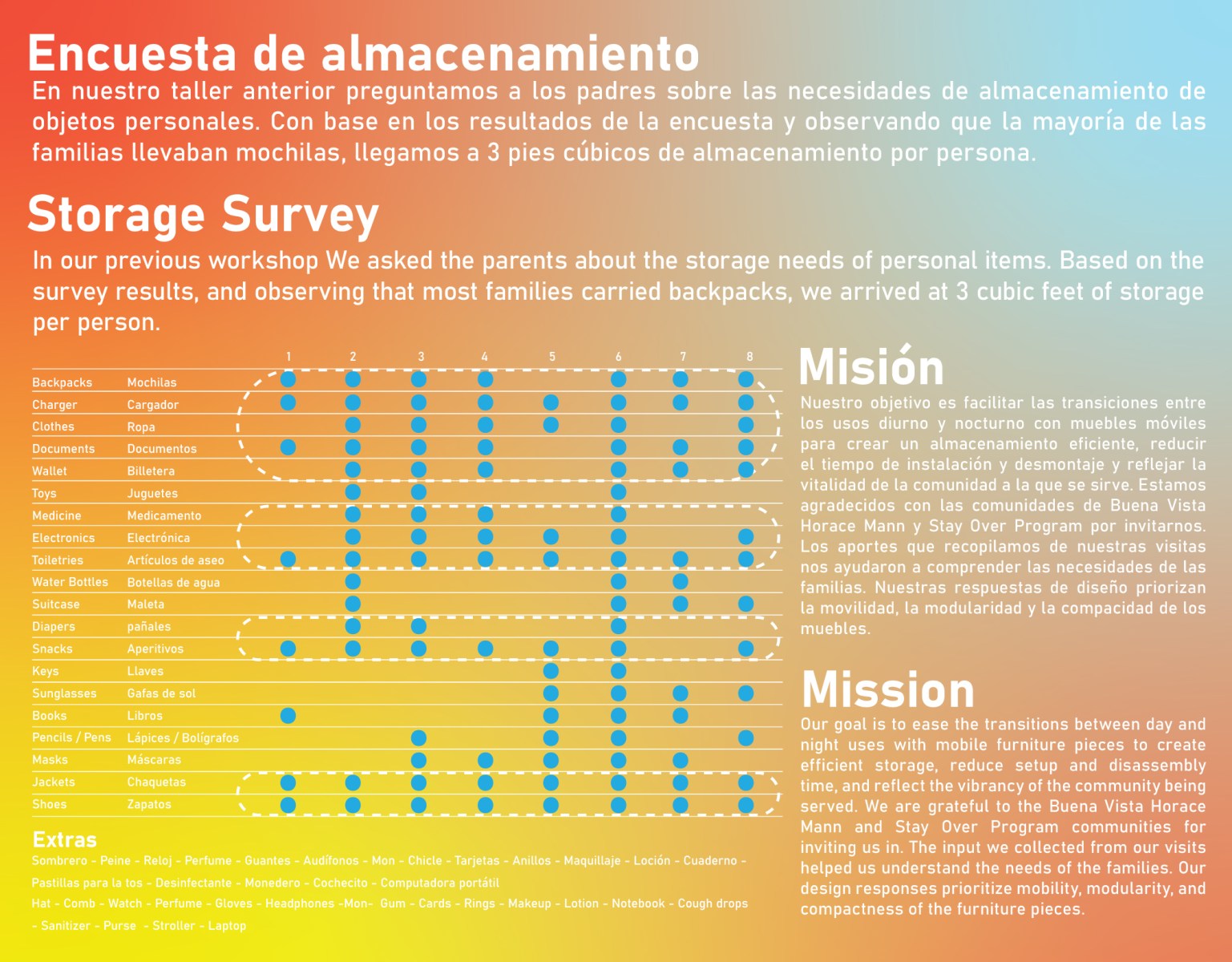

In 2023, we started a co-creation process to test how microinterventions can empower families, bring design identity to the shared spaces, and remove pain-points in the operations. Operationally, the dual use of the school gym is challenging. During the day the gym is used for PE classes and at night it is used as a shelter. The daily set up and break-down of beds is labor intensive. In addition, a severe lack of storage means that families must leave the shelter each morning and return each evening with their suitcases.

Additionally, the Stay Over Program, the most innovative component of this Community School, stays hidden from the day users of the space. The lack of visibility isn’t representative of the deep sense of community among the families.

In the absence of a design brief, we began with observations at the shelter paralleled with research on design constraints. The project scope was defined by asking what to design as well as what not to design. Physical renovations were quickly ruled out due to asbestos abatement issues.

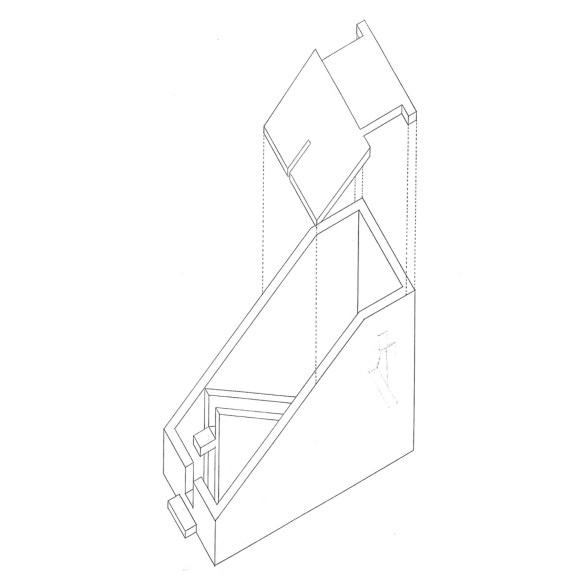

There was a long list of what “should” be done given the dire conditions at the shelter. The obvious needs of the families were overwhelming during initial visits, so the project scope was further defined by sorting must-have’s from nice-to-have’s. This process led to the decision to make 69 folding beds on wheels with storage compartments.

EMPOWERMENT THROUGH CO-CREATION

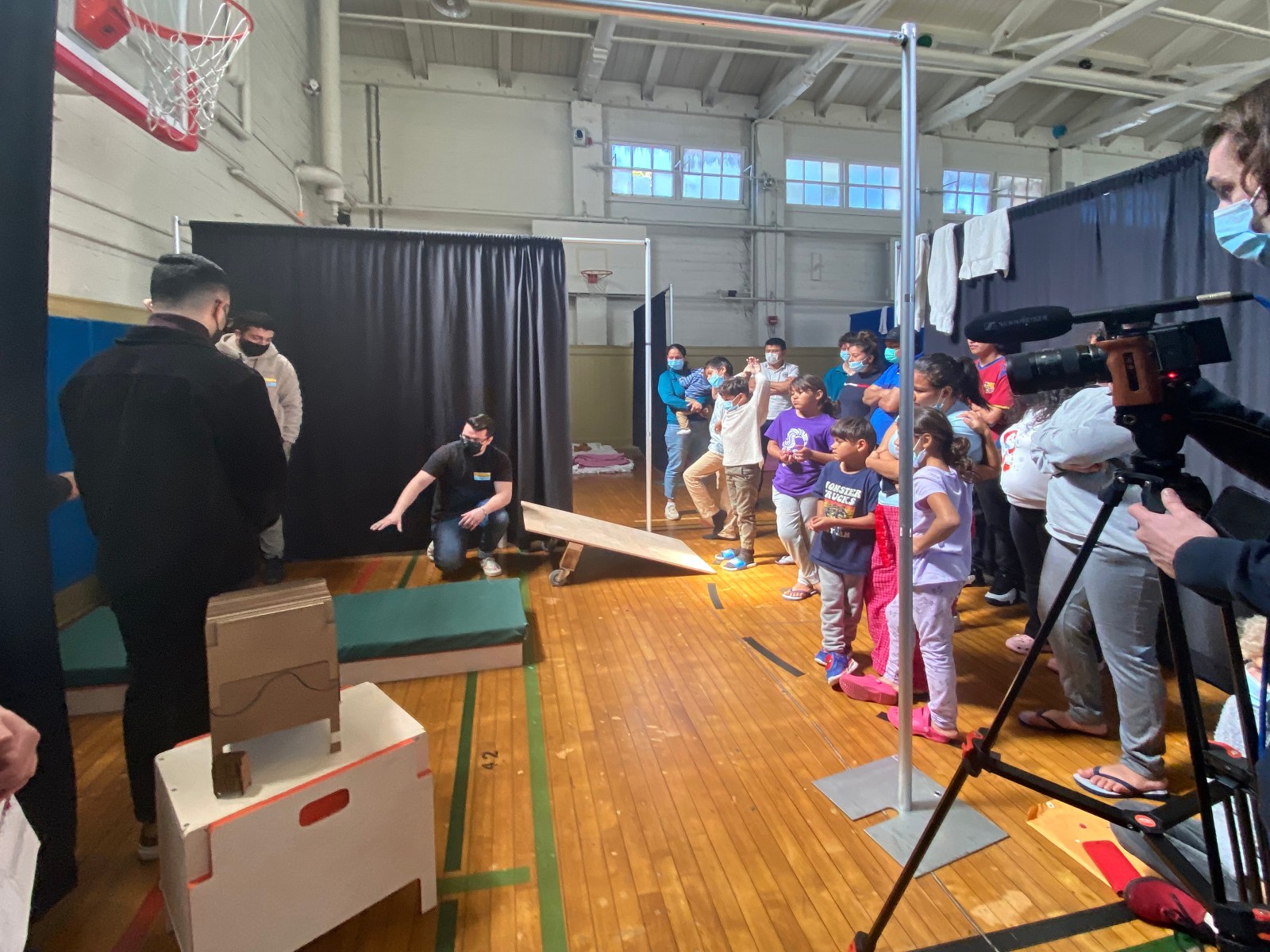

Recognizing that levels of design literacy can create a power imbalance, full-scale prototypes were used to remove barriers to co-creation. Most of the families at the shelter were not English speakers which made the prototypes the most effective means for communication providing direct hands-on experience. Parents and children offered their design input by trying out the folding bed prototypes. Simulating the daily routine using the prototypes made it possible for the families to provide valuable design insights that could only come from “situated expertise of the people.”9 An example was a compartment for shoes in the folding bed which took up too much space in the suitcases.

To build trust with the families, and with DSCS, we documented our observations and presented design proposals as direct responses. Due to fluctuations in the shelter roster, it was critical to establish clear connections between feedback from families and design responses. This video footage captures how the prototypes engaged families during community workshops.

PROTOTYPE AS EVALUATIVE TOOL

We adapted Sanders and Stappers’ three approaches to codesigning, “cultural probes, generative toolkits, and prototypes,” to the realities of the family shelter. The “generative research phase” was abridged due to the unpredictability of participants. 10 The families stay for different durations at the shelter. In between workshops, separated by months, some families had left the shelter upon being placed in housing or they happened to be off-site for appointments. Documentation of previous workshop sessions provided continuity when there were no returning participants.

EXPANDING DESIGN PRACTICES

Co-creation is not new, but it should be more widely embraced as one approach to tackle systemic problems. Paired with micro-interventions, it can reach those who are furthest away from the design process. Humility is needed to develop a co-creation method that fully benefits from widely different lived experiences.

In addition, there must be room in the curriculum for developing skills that may not align with accreditation requirements. During the “fuzzy front end” phase when project scope is being determined, design skills should be used on behalf of the co-creation team to develop tools for exploration and expression.11 Knowledge of material costs and fabrication processes will be essential to assess budget and schedule feasibilities. An added reward in working with children is the opportunity to introduce them to careers in design.

Architecture students who develop co-creation skills can lead the change to include more people we advocate for in design processes.

STUDENT REFLECTIONS ON CO-CREATION

The 69 folding beds are currently in production. Pausing to reflect on the past 8 months, students shared what they learned about co-creation:

Prototypes were compelling tools to communicate with the families. It was much more effective than diagrams. The cocreation process evealed that our assumption is not always correct. We are inexperienced in their situation. We are the tools that users need to craft their needs. (Mohamed Meawad)

Our objective was to empower the families, rekindle their sense of ownership in the use of the spaces, reestablish their visibility, and instill hope. (Andrew Hart)

Interacting with the families and getting to know them helped the project move forward. (Mazen Ghaly)

It was crucial to engage the families because they are experts in their own experiences and needs. They know the realities of living without a home and could offer valuable insights. Art and community-building activities help families feel connected to the design process. They gain a sense of control over the project’s direction and have a say in the decisions that affect their lives. When unsheltered families are seen as partners in the design process, it sends the message that homelessness is a societal challenge that we can all work together to address. (Kim Ebueng)

VIDEO STORYTELLING

On a final note, we found video storytelling an effective way to build empathy for families experiencing homelessness. At its inception in 2018, the Stay Over Program was not without its critics. There was opposition stemming from negative stereotypes associated with homelessness. Despite the skepticism, DSCS and BVHM created the warm culture at SOP that is palpable to visitors today. We invited the families to share their stories in video interviews. Tragedies rendered them temporarily unhoused, but their hopes for their children connected us. The video stories we collected helped families feel heard and highlighted the compassion and hope that the SOP program provides.

ENDNOTES

1 “Shelter Inventory,” San Francisco Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing (HSH), accessed October 10, 2023, https://hsh.sfgov.org/services/the-homelessness-response-system/shelter/

2 “Point-in-Time Counts,” San Francisco Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing (HSH), accessed October 10, 2023, https://hsh.sfgov.org/about/research-and-reports/pit-hic/

3 “Enrollment Rights of Students Experiencing Homelessness (SAFEH),” San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD), accessed October 10, 2023, https://www.sfusd.edu/services/know-your-rights/student-family-handbook/chapter-3-family-resources-and-rights/38-enrollment/384-enrollment-rightsstudents-experiencing-homelessness-safeh

4 “Enrollment Multi-Year Summary: San Francisco Unified Report,” California Department of Education, accessed October 10, 2023, https://dq.cde.ca.gov/dataquest/dqcensus/EnrEthYears.aspx?agglevel=District&cds=3868478&ro=y&year=2022-23

5 Nick Chandler, Interview with authors, January 20, 2023.

6 “$40 Million in Buena Vista Horace Mann Funding to Address Long-needed Repairs,” El Tecolote, January 12, 2022, https://eltecolote.org/content/en/40-million-in-buena-vista-horace-mann-funding-to-address-long-needed-repairs/

7 “$40 million approved for long-awaited Buena Vista Horace Mann renovation,” San Francisco Examiner, October 27, 2021, https://www.sfexaminer.com/archives/40-million-approved-for-long-awaited-buena-vista-horace-mannrenovation/article_06e34f16-84bc-5a31-a85a-bcecd396a799.html

8 “Buena Vista Horace Mann K-8 Modernization,” SFUSD, accessed October 10, 2023, https://www.sfusd.edu/bond/modernization/bvhm

9 Elizabeth B.-N. Sanders & Pieter Jan Stappers, “Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design,” CoDesign: International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts, vol. 4, no. 1 (2008): 5-18, https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068.

10 Elizabeth B.-N. Sanders & Pieter Jan Stappers, “Probes, Toolkits and Prototypes: Three Approaches to Making in Codesigning,” CoDesign: International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts , vol. 10, no. 1 (2014): 5-14, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2014.888183.

11 Elizabeth B.-N. Sanders & Pieter Jan Stappers, “Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design,” CoDesign: International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts, vol. 4, no. 1 (2008): 5-18, https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068.